Chapter 6 R recap

This section presents basic steps that are required (or simply good practice) before starting the project. It provides a brief recap of R fundamentals such as data types and structures, objects and commands. It aims at building a starting point for those who are new to R and provides background knowledge that the reader can build on, while progressing through the chapters of this book. It will be particularly useful for beginners, who have minimal knowledge of R. Therefore, more advanced readers can simply skip this chapter.

Learning objectives

- Create a new R project and start working with data

- Identify and characterise different data types and structures in R

- Access and search for help within R

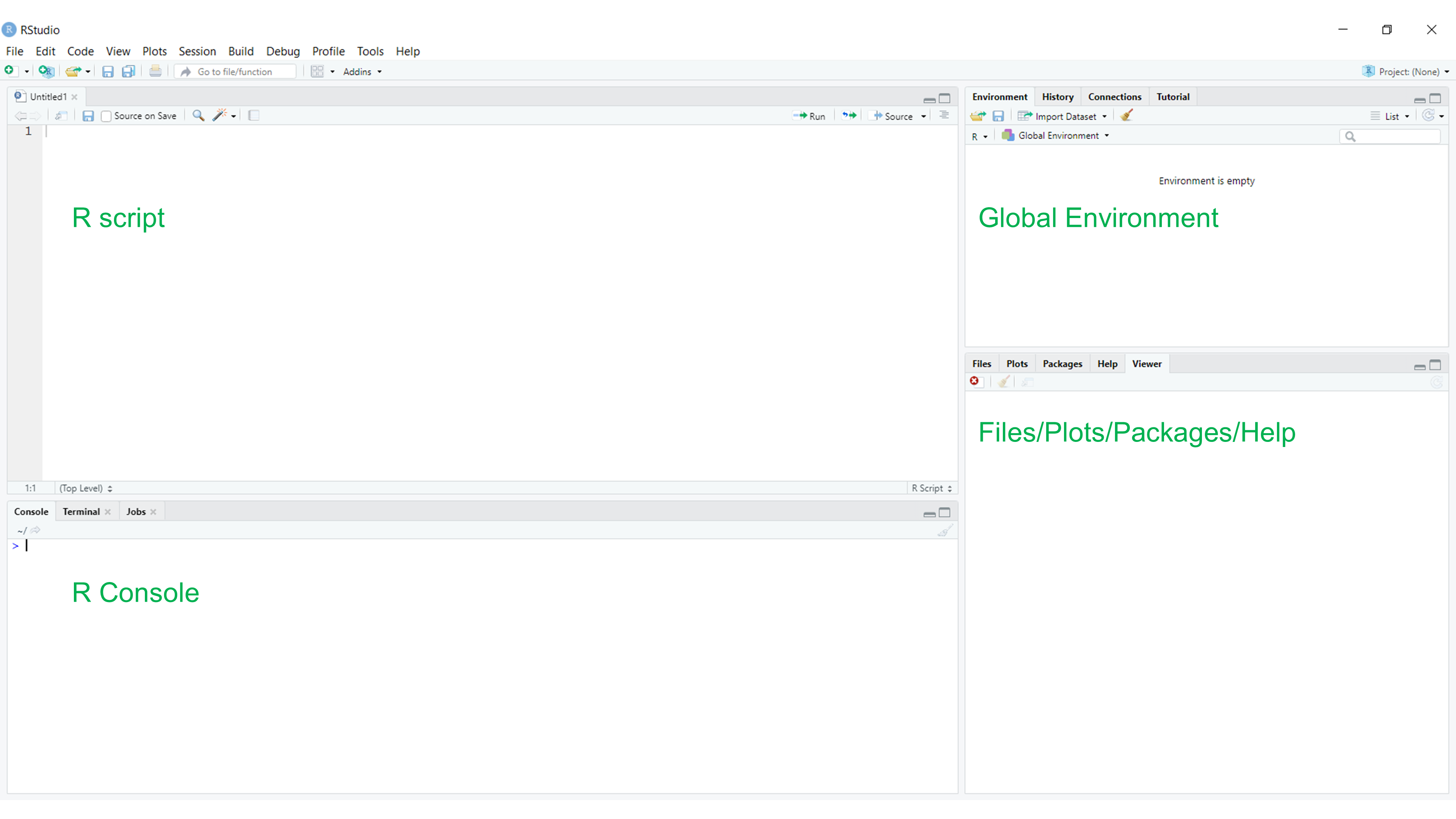

6.1 R studio window

Let’s start with basic setup of R studio window. As seen in Figure 5.1, the typical R studio consists of four elements: R script, which is a file that will contain your code, and which can be saved. Below, there is a console that will display the output of the executed code. It is also possible to type the code directly in the console, however, it will not be saved after you close current R session. Thirdly, there is so-called global environment or a workspace that will store all the objects that you currently work with, such as data frames, matrices, variables etc. Finally, in the bottom right corner you will find a panel where you can access the files in your current project or working directory, see installed packages, view your visualisations such as plot, graphs and maps and finally get help (for details on getting help, click here)

Figure 6.1: Empty R studio window

6.2 Setting working directory

At the beginning of each project it is crucial to determine the working directory of your project. A working directory is a folder where all your files associated with the project will be stored. For example, original data sets, saved data sets as well as plots, graphs or maps created and exported from R. Hence, working directory not only allows you to gather and access the files produced along the work but also load the existing data sets into the RStudio.

You can set up the working directory with the openProject function as follows (recommended):

rstudioapi::openProject("path to your directory")Alternatively, you can use the following command:

setwd("path to your directory")While the former option will set up and open the working directory for your project, the latter simply determines the default folder for each specific R script.

6.3 Creating, naming and saving a new R script

The R script is a plain text file that allows you to save the R code containing both commands and comments. Saving the R script allows you to reuse your R code and creates a reproducible record of your work. Therefore, it is good practice to create, name and save it at the very beginning of your project.

You can create a new R script by clicking the New File icon in the top right corner of the RStudio toolbar, which will open a list with different file options. Choose the R Script from the menu and the blank script will open in the main RStudio window.

Shortcut: New R script can also be opened by Shift+Ctrl+N.

You can now save your R script by clicking on the Save icon at the top of the Script Editor, this will prompt a Save File window where you can change the name of your script. Note that the file extension for R scripts is .R. At this point you can also choose a folder where to save your new file. By default, RStudio will try to save your new script in the current working directory. Once the name and file location are chosen, simply click the Save button.

Shortcut: As you work along your R script document, you can quickly save changes by pressing Ctrl+S.

6.4 Executing the code

Now that you have set up the working directory for your project and created your first R script file, we will look into ways of executing (also known as running) the code. You can execute selected chunk of code by clicking the Run button at the top right corner of the Script Editor.

Shortcut: You can also execute the selected code with Ctrl+Enter.

If you do not select any code and press Run, RStudio will run the line of code where the cursor is located. The code which has been exectued will appear in the Console, usually located at the bottom part of the window.

In RStudio it is also possible to add comments next to your commands simply using a hashtag (#) beforehand. This will stop R from executing this specific part:

3+6 # Using R as a calculator## [1] 9# 3+6This is also a convenient way to describe your R script, name different section and keep it organised. Short, descriptive headings will help you tidy up your work and will be helpful when remembering what each section does.

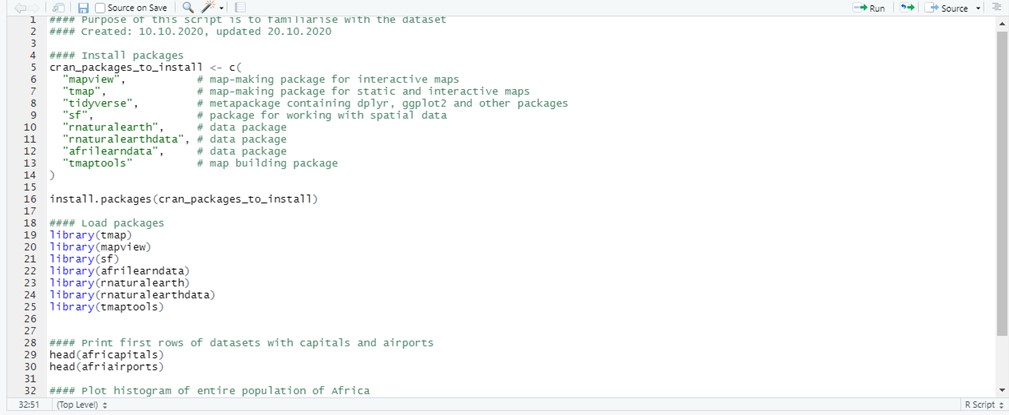

Figure 6.2: An example of an organised and annotated R script

6.5 Install and load packages

As described by Wickham & Bryan (2015) R packages are the basic unit of shareable code containing a collection of functions and data. The main repository for quality-controlled packages is Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN), but there are number of remote repositories, where packages can also be published and stored by their authors such as Github or GitLab. Packages can differ in their capabilities and they will usually have a specific purpose, for example, data wrangling, visualisations or modelling. To learn more about a particular package we can use packageDescription, which provides a brief description of a package. For example, the remotes package is often used to install other packages available at remote repositories.

packageDescription("remotes")Before being able to use a specific package in R, it is necessary to first install and then load it. Packages from CRAN can be installed with install.packages(). In this example we install package remotes using install.packages().

install.packages("remotes")After the install, we have to load the package into R using library() function in each R session that we want to use it. Note the presence of the quotation mark ("") in case of the first function and its lack in case of the second function.

library(remotes)As mentioned above, to download and install packages directly from non-CRAN repositories such as GitHub, we can use previously loaded remotes package to intall (e.g. install_github()) and after that use library as usual:

remotes::install_github("afrimapr/afrilearndata")

library(afrilearndata)In the example above, we use double-colon operator :: to call function install_github from name spaceremotes. Only functions included in the packages can be retrieved in this manner.

6.6 Load data

There are different approaches that can be used to import your data sets, depending on where the data is located and in what file type it is stored. The easiest case is when the data set is already part of the R package, as it will be automatically read in when the package is installed and loaded into R.

For example, install and load packages containing data sets:

remotes::install_github("afrimapr/afrilearndata")

library(afrilearndata)To view what data sets are available in a given package:

data(package="afrilearndata")We can view and explore the africapitals data set using the function str() which displays the structure of the data :

str(africapitals)## Classes 'sf' and 'data.frame': 51 obs. of 5 variables:

## $ capitalname: chr "Abuja" "Accra" "Addis Abeba" "Algiers" ...

## $ countryname: chr "Nigeria" "Ghana" "Ethiopia" "Algeria" ...

## $ pop : int 178462 2029143 2823167 2029936 1463754 578860 1342519 547668 34388 404119 ...

## $ iso3c : chr "NGA" "GHA" "ETH" "DZA" ...

## $ geometry :sfc_POINT of length 51; first list element: 'XY' num 7.17 9.18

## - attr(*, "sf_column")= chr "geometry"

## - attr(*, "agr")= Factor w/ 3 levels "constant","aggregate",..: NA NA NA NA

## ..- attr(*, "names")= chr [1:4] "capitalname" "countryname" "pop" "iso3c"… or the function head() which displays the first few rows of the data :

head(africapitals)## Simple feature collection with 6 features and 4 fields

## Geometry type: POINT

## Dimension: XY

## Bounding box: xmin: -0.2 ymin: -18.89 xmax: 47.51 ymax: 36.77

## Geodetic CRS: WGS 84

## capitalname countryname pop iso3c geometry

## 280 Abuja Nigeria 178462 NGA POINT (7.17 9.18)

## 308 Accra Ghana 2029143 GHA POINT (-0.2 5.56)

## 382 Addis Abeba Ethiopia 2823167 ETH POINT (38.74 9.03)

## 996 Algiers Algeria 2029936 DZA POINT (3.04 36.77)

## 1584 Antananarivo Madagascar 1463754 MDG POINT (47.51 -18.89)

## 2193 Asmara Eritrea 578860 ERI POINT (38.94 15.33)We can also create a dataframe from africapitals in the global environment:

dataset <- africapitals6.7 Basic data types

In this section we explore a basic set of possible object types that you can encounter in a dataframe. The division presented below is based on the types of values that data (object) stores. The most popular data types are:

- Numeric

- Character

- Logical (so-called Boolean)

- Factor

In R the type of object is referred to as class of an object and this function can be used to learn what data types the object contains.

x <- 11 #we create a vector that stores value 11

class(x)## [1] "numeric"It is useful to check the class of an object because each class has different properties and can be used in a different way. For example, intuitively we can perform the mathematical operations on numeric objects such that:

x <- 11

y <- 52

x * y # multiplication## [1] 572Hint: To assign a value to an object two operators can be used interchangeably: <- or =.

6.7.1 Numeric and integer

Numeric data stores real numbers. This means that the object x from above is in fact 11.000000, where the zeros are not printed, by default. It is also possible to store value as whole number in a class object called integer. An integer can be created from a numeric object in the following way:

x <- 13.5

z <- as.integer(x)

class(z)## [1] "integer"Please note, even though the numeric value is a decimal number the integer by default rounds downwards, hence both 13.1 and 13.9 will result in integer equal 13.

6.7.2 Characters

Character objects store text, usually referred to as a string. String can be a letter, word or even a sentence.

x <- "adult"

y <- "A"

y <- "I have a bicycle."Interestingly, a character can also contain a number, however it will be stored as a text and will not have the same properties as a numeric or integer object. As a results, it will not be possible to perform calculation on character objects, even if they contain numbers. This is when the class function becomes helpful.

x <- "5"

y <- 7

class(x)## [1] "character"class(y)## [1] "numeric"It is also possible to convert character variables into numeric:

x <- "5"

z <- as.numeric(x)

class(z)## [1] "numeric"6.7.3 Logical

Logical objects can take values TRUE or FALSE, where TRUE is an equivalent of 1 whereas FALSE is an equivalent of 0. In these sense, they can be thought of as numerical values.

x <- TRUE

y <- 3 + TRUE

print(y)## [1] 4Typically, logical objects are results of a condition. For example, if we want to test if object a is larger than 100.

a <- 76 #create an object a

a > 100 # condition 1## [1] FALSEa < 80 # condition 2## [1] TRUE6.7.4 Factors

Factors are categorical variables with associated levels. They can store both, numbers:

a <- rep(1:3, times=3) # create a vector of numbers from 1 to 3, repeated 3 times

a <- as.factor(a)

a## [1] 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3

## Levels: 1 2 3and strings:

b <- c("A", "B", "B", "C", "D", "C", "C")

b <- as.factor(b)

b## [1] A B B C D C C

## Levels: A B C DThe numbers and strings, in the example above, serve as labels of different levels.

Exercise 1: Create a vector ‘a’ that contains descending sequence of numbers from 50 to 30 that decreases by 2. Hint: use seq()

6.8 Basic objects and data structures

In this section we explain the basic data structures that we often work with in R. These include a vector, list, matrix and a data frame.

6.8.1 Vector

Vector is a one dimensional structure which contains elements of the same type. Usually a combine function is used to create a vector such that:

a <- c(1:10)It is also possible to create a vector with text-based objects, for example with capitals from our afrilearndata:

capitals <- africapitals$capitalnameWe can print content of our vector to see what it contains:

print(capitals)## [1] "Abuja" "Accra" "Addis Abeba" "Algiers" "Antananarivo"

## [6] "Asmara" "Bamako" "Bangui" "Banjul" "Bissau"

## [11] "Brazzaville" "Bujumbura" "Cairo" "Conakry" "Dakar"

## [16] "Dodoma" "Freetown" "Gaborone" "Harare" "Jibuti"

## [21] "Kampala" "Khartoum" "Kigali" "Kinshasa" "Libreville"

## [26] "Lilongwe" "Lome" "Luanda" "Lusaka" "Malabo"

## [31] "Maputo" "Maseru" "Mbabane" "Mogadishu" "Monrovia"

## [36] "N'Djamena" "Nairobi" "Niamey" "Nouakchott" "Ouagadougou"

## [41] "Porto Novo" "Pretoria" "Rabat" "Tripoli" "Tunis"

## [46] "Windhoek" "Yamoussoukro" "Yaounde" "al-'Ayun" "Juba"

## [51] "Hargeysa"Another important feature is to see what types of objects the vector stores. We can see that our text-based objects are characters using typeof function:

typeof(capitals)## [1] "character"6.8.2 Matrix

Matrix can be thought of as an upgraded version of a vector, where vector is an one-dimensional array and the matrix is a two-dimensional array. We can create a matrix that has three columns and five rows with the following:

matrix(1:15, ncol=3, nrow=5, byrow = TRUE)## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] 1 2 3

## [2,] 4 5 6

## [3,] 7 8 9

## [4,] 10 11 12

## [5,] 13 14 15By default, the elements in the matrix will be arranged by column, so byrow=TRUE segregates the elements in the matrix row-wise.

We can also exploit the fact that matrix is an upgraded vector by binding them column- or row-wise, as long as they have the same length:

vector1 <- c("water", "milk", "juice")

vector2 <- (1:3)

cbind(vector1, vector2) #for row-wise binding we would use rbind()## vector1 vector2

## [1,] "water" "1"

## [2,] "milk" "2"

## [3,] "juice" "3"6.8.3 Data frame

Data frame is a two dimensional array, similar to a matrix. However, unlike a matrix, it can contain different data types. In a data frame a column is a variable and row is an observation. You can create a simple data frame with two columns and three rows, using vectors above, with data.frame function:

data.frame(vector1, vector2)## vector1 vector2

## 1 water 1

## 2 milk 2

## 3 juice 3If you compare the output of the example above where we used the cbind function to create a matrix, to the result of the data.frame function, we can clearly see the difference between a matrix and a data frame. Where matrix is homogeneous and data frame is heterogeneous in terms of data type. All the values in the matrix are characters while the first column in data frame contains factors and the second one integers.

To address a specific column in a data frame we can use $ such that:

df_1 = data.frame(vector1, vector2) #create data frame called df_1

df_1$vector1 #view column called vector1## [1] "water" "milk" "juice"Columns in the df_1 have adapted names of the vectors:

colnames(df_1)## [1] "vector1" "vector2"We can change the column headers by their names or their index such that:

names(df_1)[names(df_1) == "vector1"] <- "drinks"

names(df_1)[2] <- "amount"

colnames(df_1)## [1] "drinks" "amount"Exercise 2: Create three vectors containing character, integer and logical values, respectively. Each with 10 rows. Bind them to generate a matrix with 3 columns and 10 rows.

Exercise 3: Create a data frame from the matrix created in the previous exercise. Rename column headers to describe their content.

6.9 Getting help with R Help

R is a powerful software with many different packages and functions which are continuously developed and added. Therefore, it is difficult, if not impossible, to be familiar with all the functions that are currently available. Hence, in order to learn more about them, R provides extensive documentation which can be accessed with help() function, ? operator or by clicking in Help panel in the bottom-right corner. For example:

help(matrix) #to find out what matrix isAlternatively, it is possible to use ? in front of the searched item and the R documentation will appear in right-bottom pane. For example, to read more on how to use help function itself, or the str() function we used above, we can use:

?help

?str Importantly, in order to get help regarding objects with unusual names such as the logical operators, it is necessary to use quotation marks:

?"&"

help("!")R documentation for functions frequently offers a working example which can be accessed with:

example(vector) #to see an example of a vector6.10 Further resources

Finally, the Internet also provides several reliable sources such as official R website, documentation pages, R packages book or knowledge sharing platform Stackoverflow where you can find help.

6.11 Summary

In this chapter we learned several R commands which prepared the reader for starting with his/her own project. Moreover, we familiarised with a number of data types and R objects. Moreover, we looked at how to obtain help and access R documentation. The material covered in this section aimed at building a base for the reader to allow him/her successfully progress through the book.

6.12 Exercise solutions

- Exercise 1

a <- seq(50,30, by = -2)- Exercise 2

v1 <- c("water", "milk", "juice", "coffee", "tea", "tea", "juice", "milk", "water", "soda")

v2 <- seq(1,10)

v3 <- rep(c(TRUE,FALSE), length.out = 10)

v3 <-as.logical(v3)

m1 = cbind(v1, v2, v3)

m1## v1 v2 v3

## [1,] "water" "1" "TRUE"

## [2,] "milk" "2" "FALSE"

## [3,] "juice" "3" "TRUE"

## [4,] "coffee" "4" "FALSE"

## [5,] "tea" "5" "TRUE"

## [6,] "tea" "6" "FALSE"

## [7,] "juice" "7" "TRUE"

## [8,] "milk" "8" "FALSE"

## [9,] "water" "9" "TRUE"

## [10,] "soda" "10" "FALSE"- Exercise 3

df = data.frame(m1)

names(df)[1] <- "Drink"

names(df)[2] <- "Amount"

names(df)[3] <- "Female"

df$Female <-as.logical(df$Female)

df$Amount <-as.integer(df$Amount)

df## Drink Amount Female

## 1 water 1 TRUE

## 2 milk 2 FALSE

## 3 juice 3 TRUE

## 4 coffee 4 FALSE

## 5 tea 5 TRUE

## 6 tea 6 FALSE

## 7 juice 7 TRUE

## 8 milk 8 FALSE

## 9 water 9 TRUE

## 10 soda 10 FALSE